- Dissolve the salt completely.

- Take 3 pounds of green tomatoes and quarter them.

- Put a whole head of garlic (cloves peeled and put in individually) into the bottom of the crock.

- Then, put the tomatoes on top of the garlic.

- Put two or three grape leaves in - the tannins will keep the tomatoes crisp.

- Then, pour in the brine and make sure that all of the tomatoes are covered with it; the crock came with stoneware weights that fit perfectly inside so that there is no chance of anything sticking out of the brine and attracting mold.

- After all of this, put some water inside the lip of the crock and put the lid on- this is an airlock system that works perfectly!

Total immersion in local culture that is often so obvious that it goes unnoticed, seems unapparent, but is rife with possibilities for exploration.

Discover. Understand. Expand.

Saturday, October 3, 2015

Crocking the safe

In a dark corner of the basement of my 1919 bungalow sits a crock whose interior has had the good fortune of fermenting pounds of cabbage into sauerkraut for the last few years. In an attempt to come closer to the heritage of my Eastern European Jewish ancestors, I have decided to give kraut a break and to use it to make my favorite pickled green tomatoes. I have written about these in former posts, and it may seem as though I am obsessed- true story. It's not my fault, though, as I inherited it from my parents and grandparents from Philly. Because I usually use Ball jars to make these, I am excited to see if the traditional way is better...

For this recipe, I have used the same salt to water ratio that I use for my pickled kohlrabi and beet stems: 5 tbsp salt to 2 qrts water.

Tuesday, June 9, 2015

Japanese Knotweed: Smart not hard

I have always wanted to grow rhubarb. Strange assertion, I know, but those of you who read this are aware that this whole blog is predicated on strange. Yes, I have always wanted a patch of big, green leafy rhubarb with its long thick stalks of red sourness, and I have never had any luck. Not sure why, maybe I haven't tried enough. This year, I was up for another try; before I could even put a spade in the ground, I rediscovered something that I had known about for quite a long time, but had never given any serious thought: Japanese knotweed.

I am what you would call a type A- personality: I am extremely driven, but when it comes to working, I try to work smart, not hard. All of the type As I know are incredibly industrious and seem to thrive on the work itself. I am more interested in the product. So, you might be asking yourself what this has to do with rhubarb...

I have been "foraging" since I was 10 years old and I bought my first book on wild edible plants. It looked like this:

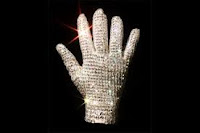

In 1983, most of the world was infatuated with one-handed sparkly gloves and jelly shoes.

Foraging was not really on most people's agendas and probably even less so ten-year-old boys, although I'm sure many kids have eaten wild plants and just not talked about it. It's inevitable when you're out playing and you get hungry.

I'm not even sure foraging was called foraging back then; I think it was just called "weird" or "grody". I mean, you go out and eat stuff that doesn't magically appear in the produce section at the grocery store? Then again, when you live in subsidized housing and don't have any money, you can be pretty creative with your spare time. The fact our complex was bounded by woods on one side helped us to pass the time.

We used to eat even stranger stuff at my house than I did in the field. My brother's father introduced us to organ meat when I was 9 (heart and kidney), although my mom had already very generously presented us the fantastic opportunity to eat liver and tongue- a vestige of her bubby's cooking back in Philly. There was milk soup with dumplings, hominy, grits. Pickled green tomatoes when we could find them, bowties and kasha. Our favorite sweet was halva, coupled with the fabled Tastykakes my aunt would send us from Philly. We pretty much ate anything that could be consumed. It's no wonder my sister and I came up with our famous pickle juice and spaghetti concoction. It's exactly what it purports to be: raw spaghetti noodles broken up and mixed with pickle juice and garlic powder. The crunch of the noodles and the acridness of the pickle juice was only enhanced by the intensity of the Aldi's garlic powder we sprinkled on the top. This was our go-to snack. Yes, we were odd, but we secretly reveled in our oddity.

After these culinary experiences, it is not so difficult for me to label something as food, and so this post comes full circle. Foraging for me is not odd, nor is it some cool trend like lacto-fermentation or buying organic. It is part of my childhood collective memory and identity. So, when given the chance to wait a year until the rhubarb grows or harvest an invasive weed, I chose the latter, of course!

Japanese Knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum) grows in abandoned lots, back yards, anywhere it can sprout its sourness and is incredibly invasive. Because of this, many of us would like to eradicate it like we would garlic mustard. Its shoots look a bit like asparagus, but not really when you compare them side by side. To me, knotweed looks like it would grow in Japan; it's got that elegant Eastern look to it. Especially when it is fully grown with its flower, it looks like it could be outside of a shinto shrine. This is what the shoots look like in early spring. They have that bamboo-like quality, conveyed by the nodes with papery sheaths:

The taste is similar to rhubarb, but not as intense and the texture is not as stringy, either. A friend who hates rhubarb tried my pickled knotweed and to her surprise, really liked it. Just another testament to my motto when it comes to food: work smart not hard. Here are some links to learn more about this amazing foodstuff:

Steve Brill's great resource: http://www.wildmanstevebrill.com/Plants.Folder/Knotweed.html

So far, my favorite way to eat knotweed has been to grill it like asparagus:

Take several spears of knotweed.

Clean them and peel them if the outer skin is too tough.

Marinate them in good olive oil and sprinkle with salt and pepper.

Grill or broil until slightly charred.

I used them to top off salmon filets. Under the salmon is wild asparagus, prepared the same way as the knotweed.

Tuesday, May 5, 2015

It's easy being green, Kermit

It's early spring and my impatience is palpable. I can't wait to go strolling for parts of my meal. During the months of April and May, plants are at their most tender stage and this is my favorite time to eat them! The greens produced during this period can be bitter, but they are nutrient-rich and no one can beat the freshly culled green treats that await those of us who know about them. I have been foraging for greens and other plants since the early 80s when I was a mere child; unfortunately it took quite a long time for me to develop the taste required to really enjoy these greens. I am dedicating this post to winter cress because it has quickly made its way to the top of my list.

The pic below shows three of my favorite early spring greens: Winter cress, peppergrass and plantain (left to right and top to bottom).

To harvest this plant is extremely easy: pick the leaves closest to the top, as they will be less bitter than the large ones at the bottom of the plant. For the flower buds, just cut them at the base of the stalk, with the leaves still on the stalks. Put them in a plastic bag in the refrigerator until you need them; check on them if you don't plan on using them right away, as they can become flaccid and wilted. Just soak them in cold water for a while and drain them to fresh them and then store them in a freezer bag in the crisper. The possibilities for cooking and eating these beauties are endless and I suggest experimentation for anyone who likes to cook. You can use the leaves, flower buds, and stalks in recipes that call for greens - especially those that require mustard greens, as they are bitter, too.

Click the tofu for a recipe that winter cress will make even better!

The pic below shows three of my favorite early spring greens: Winter cress, peppergrass and plantain (left to right and top to bottom).

Winter cress is a hardy plant that grows literally everywhere I walk in Milwaukee. I have seen it in old garden beds, along bike trails and even in yards. It has very shiny, dark green leaves and at this point in the season has grown stalks with flower buds that resemble very small florets of broccoli. These are very bitter when eaten raw, as are the leaves; when cooked, however, they become very palatable to anyone who likes greens and I highly recommend them.

Pic from (http://www.rhodysurvivalist.com)

Click the tofu for a recipe that winter cress will make even better!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)